3BI: Behavioral Science of AI

Welcome to my 3BI newsletter, where I share three insights from the world of behavioral science on psychology, decision-making, and behavioral change.

Did someone forward this newsletter to you? Sign up here to have every new edition delivered straight to your inbox.

I’m a bit of a late adopter when it comes to AI. Since the launch of ChatGPT, I mostly dabbled with LLM’s occasionally without finding a core use case that kept me coming back regularly.

In the last couple months, that’s changed, though. I use ChatGPT daily and, often, throughout the day. What changed was less of a specific thing that I found useful, but a clearer perspective on when and how to use it (rooted in behavioral science, of course). Here are the key aspects of that perspective along with their respective behavioral science principles.

Satisficing

Satisficing is a decision-making strategy that involves choosing the first option that meets a minimum set of criteria, rather than searching exhaustively for the optimal or "best" solution. Basically, it’s when we aim for “good enough” rather than “optimal.”

For example, imagine you're craving a burger for dinner. A satisficer might search for restaurants in their neighborhood and quickly pick the first one they find decent reviews and a burger on the menu. A maximizer would do an in-depth search for the highest rated burger within driving distance and choose the highest rated one with the most robust menu.

I think that current AI tools are great for satisficing. When I just want to get something simple done quickly or need basic information, it’s incredibly useful.

For example, if I’m putting together a presentation and want to introduce some basic behavioral science concepts, ChatGPT can quickly write up definitions, examples, and some references that I can immediately verify and use. Such content doesn’t require creativity or deep analysis, but just serves a simple function.

If I’m doing a more in-depth report on a topic, though, I would need to dig into source material myself and craft my own perspectives and inputs.

Behavioral Activation

What AI would be very helpful with for that report, though, is getting started.

Often, the behaviors we struggle with the most are those of activation. The most difficult part of running isn’t necessarily huffing and sweating through the miles, but getting up, putting our shoes on, and walking out the front door.

Psychologists call this Behavioral Activation. Originating from depression treatment, it focuses on doing before feeling and that acting first triggers positive reinforcement and momentum. The basic idea is that action precedes motivation, not the other way around.

I’ve found AI tools extremely useful for overcoming the activation barrier for tasks and projects.

For one, it helps remove uncertainty and clarify what actually needs to get done. Often, we only have a vague idea of what the task is and how to get it done. When faced with uncertainty about outcomes, processes, or expectations, we often default to inaction rather to avoid the discomfort or the effort needed to gain clarity. Ever had a task you put off for a long period of time that ended up being surprisingly easy when you finally tackled it? You probably avoided it because of some sort of ambiguity that felt easier to ignore. If we felt confident about how simple it would be, we probably wouldn’t put it off!

AI is helpful because it greatly simplifies the process of clarifying tasks. For one, it’s a captive audience personal to you. One of the best ways to overcome ambiguity is to explain the task to someone else. This simple action forces us to get out of our own heads. Just the process of typing out what you want to do, formulating questions, and responding to follow-ups is also incredibly useful in translating something from a nebulous idea to a fully formed project.

It’s also pretty good at actually starting tasks or projects for you. Even with needs and objectives clear, the blank page can be intimidating. It’s much easier to edit or build on a rough draft of something than it is to create that draft in the first place, so asking AI tools to make a first version can be a huge time saver.

An example tying these together is writing extremely personal communications, like birthday cards, wedding speeches, or eulogies, which has become a common use case. The idea of using AI for very intimate occasions like these sounds kind of creepy at first, but it makes sense when you break them down. These activities are hard to start because we lack an existing process due to their infrequency (something like a wedding speech or eulogy is something you may only do once). They’re emotionally wrought and there’s a lot of pressure to get them right. Asking an LLM to write a first draft using some personal criteria eliminates the ominous blank canvas and gives you something to build on for the final product.

Personal Assistants at Scale

These are both big elements of what I’ve found to be the best use case for AI: acting as a personal assistant and analyst.

Imagine you had someone who could act as a 24/7/365 executive assistant. What would you have them do for you? How would you make requests of them? That’s basically how I’ve started using AI.

AI tools aren’t particularly advanced in many skills yet and still make a lot of mistakes or produce incorrect information. They aren’t creative and struggle with complexity.

They’re great at straightforward, well-defined tasks with clear rules and guidelines, though. They can get to a functional level that you’d expect from entry-level or administrative support staff relatively quickly in most areas.

This makes them a fantastic accelerator that can increase output by handling grunt work and drudgery to allow for more time and energy to focus on higher value activities. This is the framing that’s gotten me over the hump of using these tools and making them a regular part of my workflow.

I think this is the type of impact it will have on industry and the economy in the next 5-10 years, as well. It won’t replace the need for expertise, experience, empathy, or creativity, but will actually make those traits more valuable as tedious grunt work is outsourced to machines.

Other Stuff

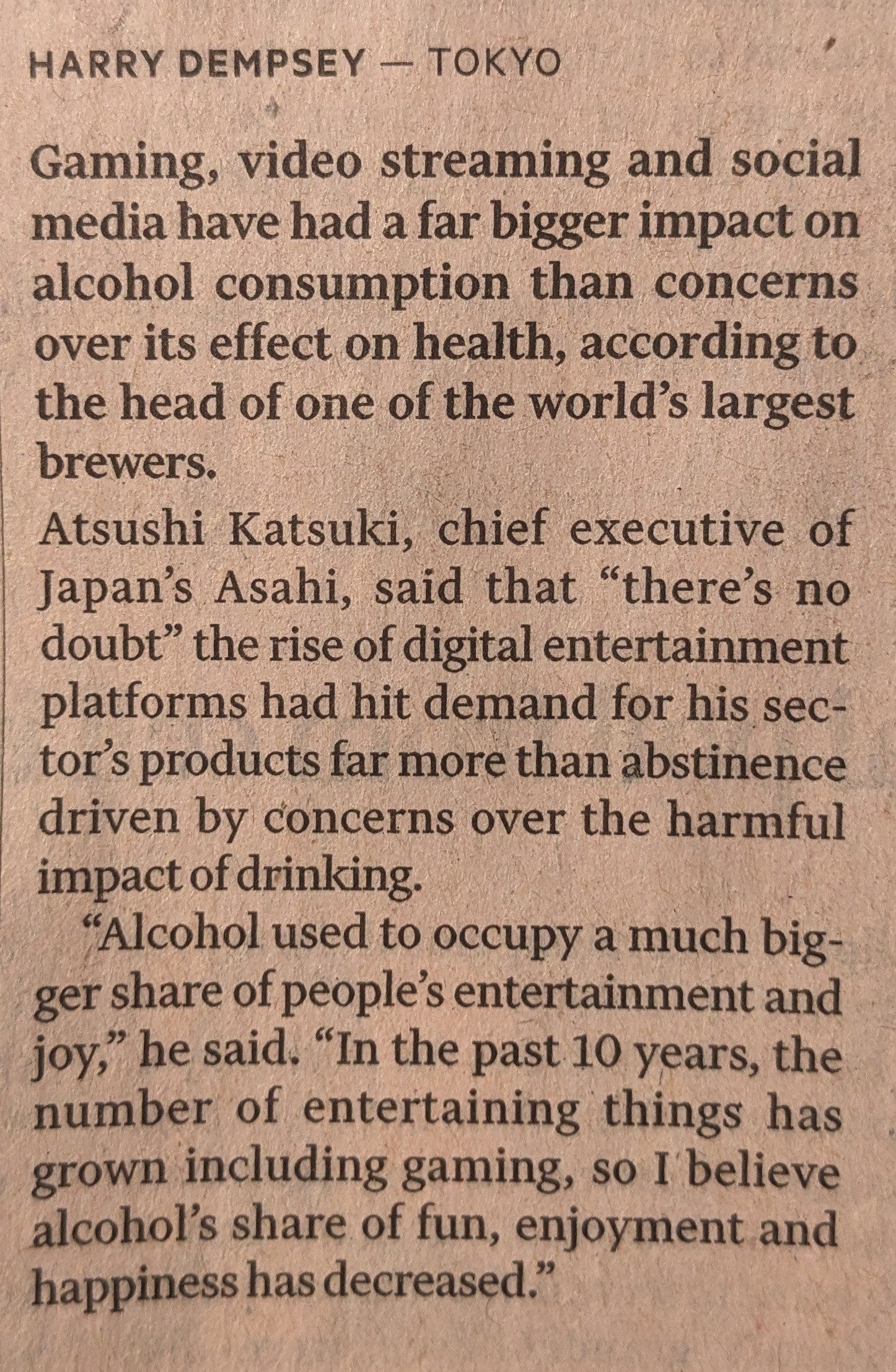

Alcohol consumption has been consistently dropping, with Gen Z notably drinking less than previous generations. The surface level explanation is that it’s related to health concerns, but the CEO of Japanese brewer Asahi thinks it has more to do with increasing options for solitary entertainment like gaming (link to FT article):

I love this defense of social science by economist Matthew Hennessey in the WSJ (gift link):

…somehow the discussion descended into a debate over a familiar question: Is economics a science?

The question isn’t helpful. Embedded within it is a faulty assumption—that observations about the world emerging from the hard sciences are somehow superior to or more useful than observations emerging from other academic disciplines. Simply, if economics is science, then it’s real and we’re bound by it. If it isn’t science, anything goes. We’re free to build a brave new world.

…

Science, properly understood, is both a body of knowledge and a process of discovery and refinement. It’s never settled. That doesn’t mean we don’t understand certain laws of the physical world like gravitation and conservation of mass and energy, or how atoms combine to form molecules. We do. Something could come along to disrupt our understanding of these basic physical realities. We have to be open to that possibility. But it’s unlikely.

That was my point about supply and demand. Two hundred and fifty years after Adam Smith, we understand how these laws of economics work. They aren’t imaginary or a human invention. They don’t change. Mess with them and you’ll lose.