3BI: Coffer Illusion, Subscription Psychology, and Non-Proportional Thinking

Welcome to my 3BI newsletter, where I share three insights from the world of behavioral science on psychology, decision-making, and behavioral change. Sign up here to have every new edition delivered straight to your inbox.

I’m back home in Chicago after a vacation to the UK over the last week and half. We visited some family in London and relaxed in Scotland with stops in Edinburgh and Inverness.

Things were hectic before the trip, but I’ll be settling into a more regular schedule now with (mostly) weekly editions of the newsletter. Onto this week’s edition:

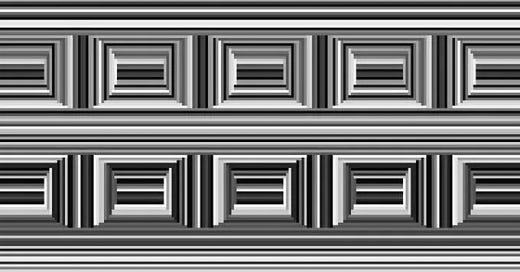

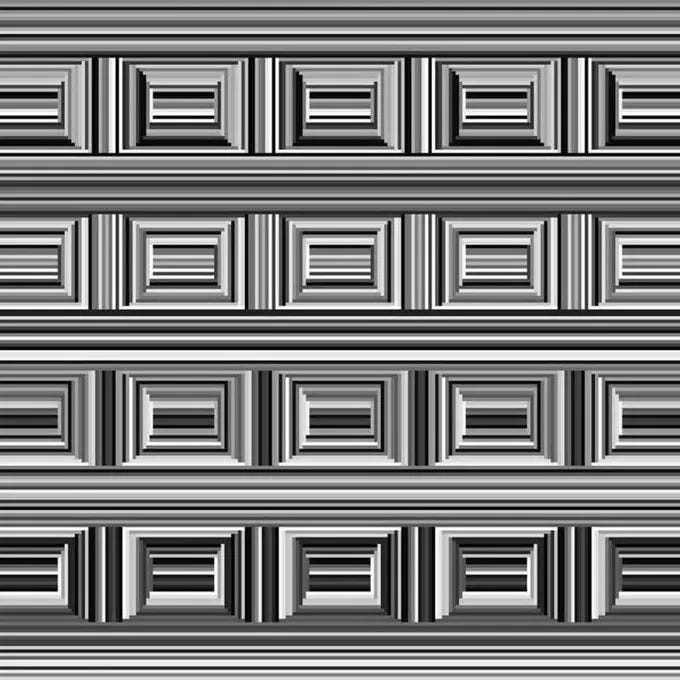

The Coffer Illusion

Take a look at the image below.

Do you see rectangles or circles?

Your answer may be dependent on the surrounding environment. In a study, researchers found that 80% of people in the U.K. and U.S see only rectangles, while around 19% see rectangles and then circles. In Namibia, however, 48% only saw circles and another 48% saw the circles first and then rectangles. Personally, I saw rectangles and had to look pretty hard before noticing any circles.

What causes such a drastic difference in how different people can view the same image? The hypothesis is that our view is driven by the environment around us. In modern urban environments, we’re inclined to notice the squares because we see a lot of neat, clean edges in objects around us, like computers, buildings, and tables. In a natural environment surrounded by nature, such precise measurements don’t exist. Instead, everything is jagged with curved edges, so our eye is trained to notice the circles.

This illusion is another reminder how much the environment around us impacts how we see the world.

Image via Behavioral Scientist.

Subscription Psychology

Do you feel like you’re paying for an increasingly large amount of subscriptions every month? You probably are, and the number is likely higher than you think. From the WSJ:

The consulting firm West Monroe surveyed thousands of Americans in 2021, asking them to guess how much they spent each month on subscriptions. Their average response was $62. When they were given more time to guess again, they increased their estimate to $96. They were still way off. The correct answer was $273.

Yikes!

Subscriptions hit a sweet spot of consumer psychology that makes them convenient and useful enough to keep signing up for, but are mostly advantageous to the companies selling them.

On the consumer side, subscriptions do simplify our decision-making. For many services, we’d rather make one decision and purchase than have to keep doing it every month. There can be budgetary benefits to spreading costs out through the year rather than in a lump sum and sometimes it helps to make a longer commitment to something we want.

Those benefits have downsides, though. The simplicity of making one up-front decision also means that we don’t have to pay attention to it after the fact and most of us don’t have a natural ability to keep track of each individual service’s cost and how much we use actually them. Canceling is also a more effortful task with less urgency than enrolling. We sign-up because there’s something we want now, like a new show or football game, but canceling is rarely a top priority, making it easy to put off.

Of course, these are the exact reasons the business model is so ubiquitous:

…paying for the subscriptions you use is not the only reason your bill is probably much higher than you realize.

It’s also because you’re overpaying for the ones you don’t use.

That, as it turns out, is one of the hidden forces behind the subscription economy: Americans spend billions of dollars on stuff they have forgotten about. A dirty little secret behind many of the world’s most popular subscription services is that they owe part of their success to our lack of attention.

Subscriptions aren’t the only way companies profit off of our inattention and forgetfulness, either. Gift cards work the same way. According to SatPost, Starbucks has made $1.2 billion over the last decade from unused balances on gift cards or their app. This is so common that such so-called “breakage” revenue is growing at a faster pace than their actual sales.

There’s a clear intention-action gap here. I don’t think many people intend to have so many subscriptions that they underestimate their monthly cost by 78% or to give Starbucks free money. What can we do about it?

For one, forced attention to the costs at some regular interval helps drive action. In a clever study, economists measured the impact of credit card replacement on subscriptions, as that’s a rare event that forces us to manually update each one, and found that the services’ renewal rates were four times lower after the card replacement period than in typical periods. We don’t need to get a new credit card every year, but setting some consistent times to review and update our subscriptions helps. The FTC is even proposing rules to require companies to send annual reminders of their subscriptions to customers, which would help alleviate the mental burden on consumers.

We can also re-frame our decisions when signing up for these services. Instead of anchoring to the lower monthly cost, we should calculate it’s annual total. The $9.99 monthly price may sound reasonable, but the $119.88 annual total can prompt a different cost-benefit analysis.

It can also help to test out the service before committing to a recurring membership when possible. For example, if you want to start exercising more, try buying day passes at the gym first to see how often you actually end up using it and only sign up for the membership once it becomes sticky enough to justify the regular expense.

Non-proportional thinking

Below are mortality statistics for two types of cancer. Based on this data, which type is riskier?

A - 1,286 people die out of 10,000 diagnoses

B - 24 people die out of 100 diagnoses

The correct answer is B, as it kills a much higher percentage of those diagnosed (24%) than A (12.8%). However, in a study using this exact scenario, participants rated cancer A as riskier. Why? Because of the way the numbers were presented. It’s easier to notice and compare the absolute number of deaths displayed in the numerator than to calculate the ratio or percentage.

This is an example of non-proportional thinking, when we evaluate data using the wrong units by focusing on absolute numbers rather than percentages.

In the business world, this means that investors may view stock price reactions to news in dollars rather than percentages. From Yale Finance professor Kelly Shue:

…in finance and in the stock market, people should be thinking about returns. And returns are basically ratios — it's the dollar change divided by the share price as of the previous day. But if people neglect the denominator and they only focus on the numerator, which is the dollar change, then they might react the same to stocks that are otherwise identical, but trading at different share prices.

…

For example, if there's good news that a skilled new CEO has joined, investors should think this firm's value will go up maybe one percent. The wrong way to think about it, and that would be non-proportional thinking, is, ‘well, other times when firms had similar good news, they went up about a dollar. So, this firm should also go up in value by a dollar per share.’

To avoid this, we need to ensure we evaluate information using consistent units. In the cancer example, the ratio or percentage is what matters, but the different levels of units confuse us. Information should also be presented in ways to avoid this bias. For example, price changes for stocks or swings in major financial indexes like the Dow should be shown as percentage changes rather than dollar or point totals.

For more, check out Milkman Delivers and Kelly Shue’s research.

Thanks for reading and see you next week!