3BI: Growing Intention-Action Gap, Doorman Fallacy, and the Human Premium

Welcome to my 3BI newsletter, where I share three insights from the world of behavioral science on psychology, decision-making, and behavioral change.

Did someone forward this newsletter to you? Sign up here to have every new edition delivered straight to your inbox.

I recently recorded a podcast with my friend Alex Birkett of Omniscent covering a wide range of behavioral science related topics. It was a lot of fun and we covered some interesting stuff that I’ll dive into more in this edition of the newsletter (though I realized my podcast skills are a little rusty after cringing at how often I said “like” in the first section).

Check it out below or on Omniscent’s blog, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.

Here are some additional thoughts on a few topics we covered:

The Widening Gap Between Intention and Action

The intention-action gap refers to the discrepancy between an individual’s stated intention and their actual behaviors.

When we fail to follow through on our goals or desires, we have a disconnect between our intentions and resulting actions.

I’ve been developing a theory that our modern environment is becoming more and more misaligned with our psychology and creating a greater intention-action gap.

Evolutionary mismatch refers to the phenomenon where traits that were previously advantageous in our ancestral environment become maladaptive in our current, rapidly changing world.

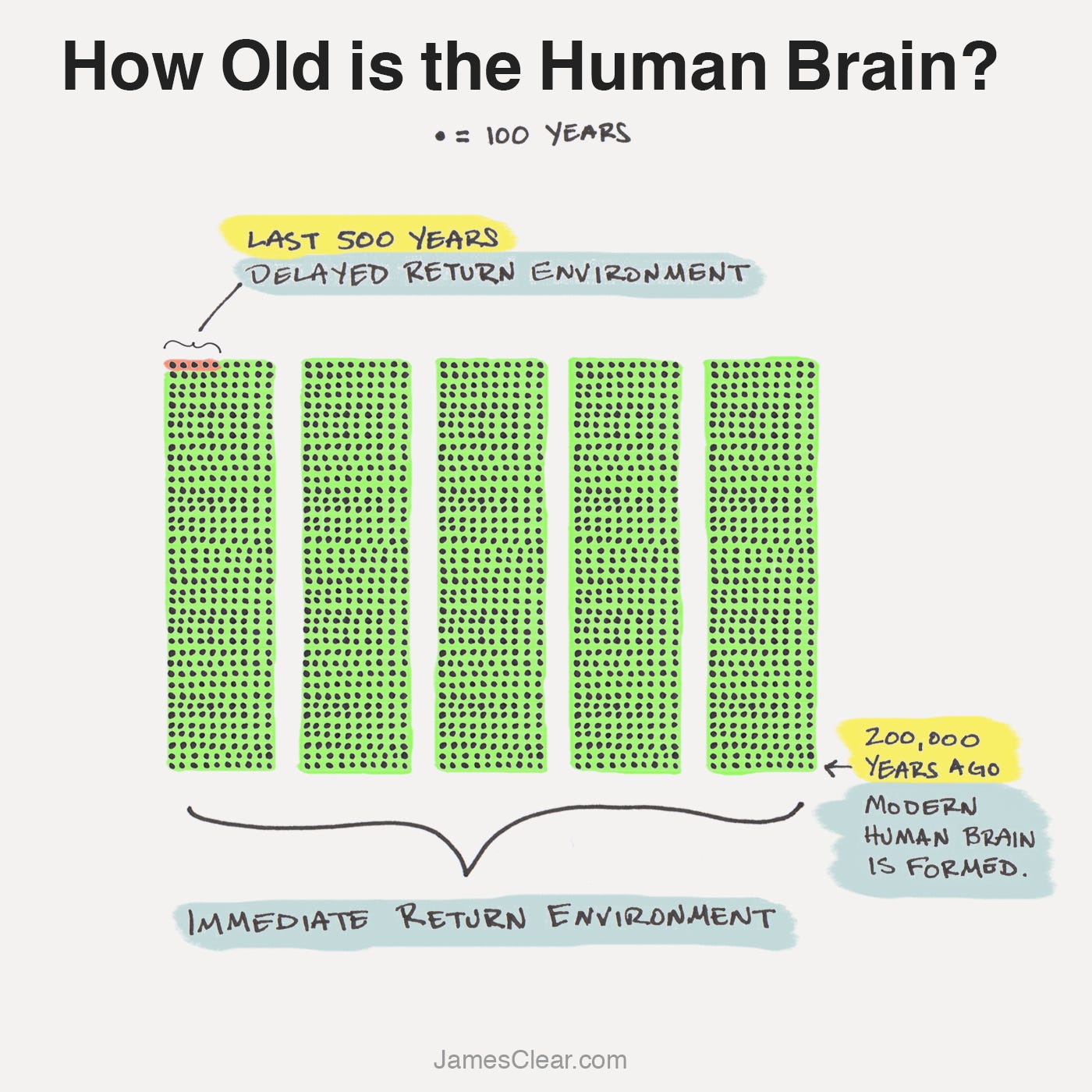

The physical structure of our brain largely evolved to its current form around hundreds of thousands of years ago, and while it continues to slowly adapt, the world around us has changed in drastic ways. Thus, our minds are largely designed for a very different environment than we find ourselves in today.

A major shift in this misalignment occurred in the last century that disrupted our physical health. As the economy became more oriented around knowledge work, cars became the predominant means of transportation and industrial food production made high-calorie processed foods cheap and widely available, making us increasingly sedentary and overweight.

Physical activity was no longer a natural part of our day and unhealthy foods became the easiest and most economical option for sustenance, so exercise and nutrition became things requiring effort that doesn’t match our brain’s wiring.

I think we’ve hit a similar inflection point with our mental health and fitness. We’ve increasingly lost control of our attention and focus with the evolution of modern media and technology.

Phones, social media, streaming services, and the like are hyper optimized to capture and keep our attention over more productive or fulfilling activities. Deep work, reading books, learning new things, or even just watching a movie uninterrupted all take active effort to do over responding to emails, surfing social media, or watching TikToks.

This has consequences for our mental health, as satisfying and enriching activities are replaced with mindless ones, and our mental fitness, since our brains need focus and healthy stimulation to stay sharp and healthy. The advancement and proliferation of AI is likely to accelerate this trend.

Just as we learned to develop exercise routines and diets in the last century, we’ll likely have to do the same for focus, enrichment and learning in the current era.

The Doorman Fallacy

Imagine a new CEO takes over a hotel chain and is tasked with cutting costs. He finds an obvious candidate in doormen: why pay for someone to open the entry door for guests when they can do it themselves or it can be automated by technology?

The decision makes sense from a purely economic or utilitarian perspective, but doesn’t account for intangible benefits or psychology.

A doorman improves the guest experience by providing a friendly face welcoming guests to the hotel, assisting with things like handling luggage or hailing taxis, and providing an extra layer of security.

They also alter the perception of the property, as we associate such staff with higher end luxury experiences. Getting rid of the doorman may result in lower costs, but can also harm reputation and guest satisfaction.

This is the Doorman Fallacy, where we make decisions based solely on immediate, measurable outcomes in a quest for short-term efficiency and cost-savings while overlooking hidden benefits and long-term value.

This concept is especially relevant with the rise of AI. Computers are increasingly able to complete tasks that humans do, but that doesn’t mean they can create the same value or experiences.

The Human Premium

The distractions of our modern environment and the threat of increased automation via AI present real challenges, but also opportunities. I think the competitive advantage of building things that align our intentions with actions and utilize human interactions will only grow.

For one, we’re social animals that have a deep need to be around others and will always put a premium on collective experiences. For example, robots may be able to make food as well as any chef at some point in the future, but that’s more likely to impact McDonald’s than Michelin star restaurants. Dining out is about the experience more than the food and being served by people is a big part of that.

Also, satisfaction is a long-term moat. We may spend hours a day on social media because of its addictive nature, but we’re rarely satisfied with that time. We’ll always be on the lookout for ways to reduce our time doing things that hijack our focus or attention, but will be more loyal to those that respect our intentions.

Finally, there will always be hidden, hard to measure advantages to the human touch. I loved how Ben Affleck described this when discussing the impact of AI on entertainment. Creativity and taste are impossible to measure and accurately plug into an algorithm.