3BI: Independence Day, Democracy Paradox, and Tyranny

Welcome to my 3BI newsletter, where I share three insights from the world of behavioral science on psychology, decision-making, and behavioral change.

Did someone forward this newsletter to you? Sign up here to have every new edition delivered straight to your inbox.

Happy Independence Day weekend to those of us here in the US! Some holiday related thoughts and insights to ponder before the long weekend.

Standing up to Tyranny

Independence Day celebrates the American Revolution’s success in fighting the rule of the British empire. What exactly drives someone to muster the courage to fight tyranny?

Psychologists and sociologists have studied the determinants of such heroism against oppression. One well studied example from semi-recent history is Europeans who protected Jews during the second world war. In that research, no clear personality indicators emerged. From Tim Harford:

…these studies of heroic acts don’t find many indicators of a heroic personality type.

“A resistance hero could be shy or self-assured, silly or serious, young or old, pious or scandalous, rich or poor, leftwing or right,” writes Bregman. There were some predictive factors, such as independence of spirit. But the heroes seemed much the same as anyone else. The only obvious distinction was the vital one: they took extraordinary risks to save others, while others did nothing.

Rather than some distinct aspects of personality or character, such courage may be more of a matter of circumstance:

A later analysis by sociologists Federico Varese and Meir Yaish focused on a different set of explanations. What if, rather than a matter of personality, courageous altruism was a matter of circumstance? And there was one circumstance in particular that stood out in the data: people who were asked to help almost never refused. The secret to being a hero? It was to have someone standing in front of you, demanding heroism.

In Nieuwlande, that person was often Arnold Douwes or his friend Max Léons, a two-man resistance army. On one occasion, Arnold and Max dropped in for coffee with a farmer and his wife, and soon raised the question: would they hide a pair of Jews from the Nazis?

As the farmer started to protest, Max breezily announced, “They’re man and wife — very sweet people . . . just a moment, I’ll go get them.” A moment later, they appeared. Max and Arnold stood up, “So, that’s settled. Good night!”

How rude. How presumptuous. But the Jewish couple survived.

Similar conclusions were found for the Freedom Summer project of 1964, in which unpaid, mostly white volunteers travelled to the Deep South to support civil rights efforts despite facing intimidation, serious violence, or even murder:

Like those who sheltered Jews from the Nazis, these were people voluntarily running mortal risks. Hundreds persisted, but hundreds of others, understandably, dropped out. What distinguished these two groups was not commitment to the cause — they were all committed — but close personal connections to other volunteers. It’s harder to quit, and easier to be brave, if you’re with friends.

Perhaps the greater question, then, is not what leads to bravery against tyranny, but what allows injustice to fester in the first place. If heroism is driven by circumstance and personal connection to the injustice, then apathy and acquiescence may be caused by disconnect. We’re naturally wired to be on the selfish side, so views of tyranny may mostly be driven by what affects us personally.

This is shortsighted, though, as injustice rarely stays isolated. Indeed, tyrants know to begin their power grabs with the downtrodden, overlooked, or undesirable because most will ignore it. Once oppression is normalized for one group, it becomes much easier to expand its reach.

Further, injustice makes everyone worse off. Countries without well-functioning democracies or robust civil rights are notably poorer and have worse quality of life than those that do. In purely economic terms, humans are incredibly valuable and productive, so societies that allow wildly uneven distribution of rights or opportunities are deliberately throttling their most valuable asset.

As we prepare to celebrate Independence Day in the US, we should be grateful for the freedoms we have while empathizing with those who are less fortunate, especially as some communities don’t feel safe enough to even celebrate the holiday this year. How would we feel in that situation? What would we do if those affected were standing before us?

The Paradox of Democracy

On the Fourth of July, we celebrate the US’ independence and its establishment of one of the world’s most robust and longest running democracies. What do we actually mean by the term democracy, though?

One of the most interesting books I’ve read recently is The Paradox of Democracy: Free Speech, Open Media, and Perilous Persuasion by Zac Gershberg and Sean Illing, which argues that democracy is not a specific type of government or bundle of institutions, but rather a culture of radically open communication.

Democracies can be liberal or illiberal, populist or consensus based, but those are potential outcomes that emerge from this open culture. And the direction any democracy takes largely depends on its tools of communication and the passions they promote.

We call this the paradox of democracy: a free and open communication environment that, because of its openness, invites exploitation and subversion from within. This tension sits at the core of every democracy, and it can't be resolved or circumnavigated. To put it another way, the essential democratic freedom - the freedom of expression - is both ingrained in and potentially harmful to democracy.

…

Democracy is dangerous for precisely this reason, which presents not just a collective-action problem but a genuine existential dilemma: it demands that we take responsibility for the situation in which we find ourselves. Democracy has no defined purpose, and it is shaped in real time by the communicative choices of individual citizens and politicians. But it offers no guarantees of good governance or just outcomes.

I think this is an interesting shift in perspective. We tend to think of democracy (or other systems of governance) as a tangible entity with defined processes, institutions, and outcomes, but it’s really a dynamic culture that can be pulled in a wide variety of directions. The form of that culture is driven by the public and its forms of communication, from newspapers to Tik Tok videos.

National Identities

The Power of Us has an interesting post on how different forms of national identity can be healthy or harmful:

What it means to be proud of one’s country depends on how we think about our national identity. And national identity, as it turns out, can take many forms. One key distinction lies between healthy, secure national identity—rooted in civic values, solidarity, and genuine care for one’s fellow citizens—and a defensive, superficial one, more concerned with appearances and external recognition than with what the country stands for or how its people are actually doing.

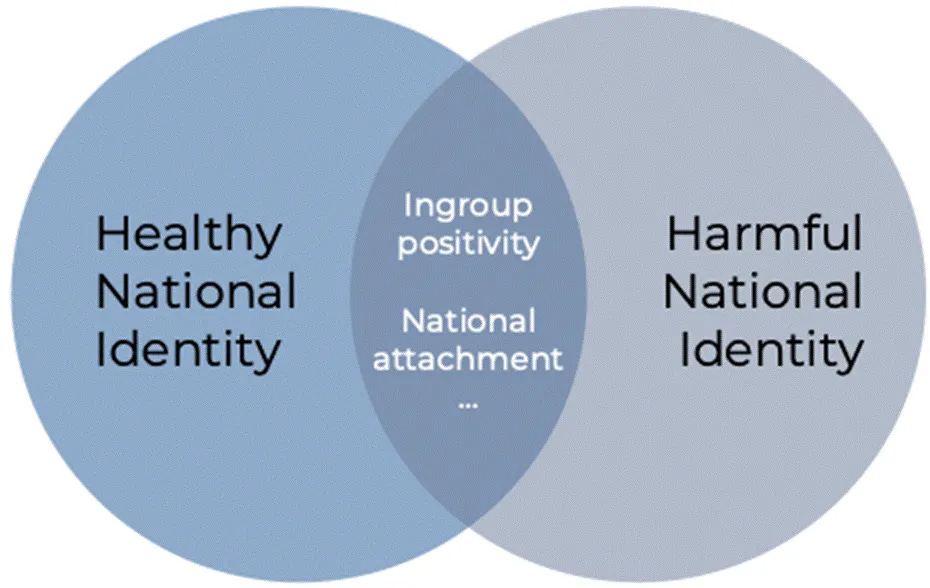

They identify two competing identity types with some overlapping characteristics:

Pairing this idea with the paradox of democracy, we can see how national identities can form and change over time via shifting cultures of communication and debate.

Read more at the Power of Us.