3BI: Knightian Uncertainty, Dual-Inheritance Theory, Chicago BeSci event

Welcome to my 3BI newsletter, where I share three insights from the world of behavioral science on psychology, decision-making, and behavioral change.

Did someone forward this newsletter to you? Sign up here to have every new edition delivered straight to your inbox.

Happy Friday everyone!

We're hosting another Bescy event at Mindworks next week here in Chicago. If you’re in town, come hang to connect with other behavioral science enthusiasts, get a guided tour of the Mindworks facility, participate in real lab experiments, and check out interactive exhibits. Info and registration here.

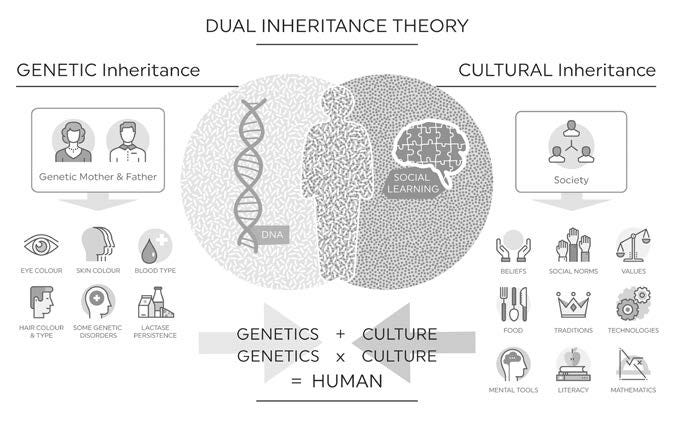

Dual-Inheritance Theory

What drives who we are: nature or nurture? The answer is both, and it’s part of what makes humans unique.

Dual inheritance theory explains human behavior as a product of two different and interacting evolutionary processes: genetic evolution and cultural evolution.

The idea is that our actions are formed by two primary inputs: our genetic makeup formulated by millions of years of evolution and cultural influences provided by the society around us. The latter is what truly differentiates us as a species. From Michael Muthukrishna:

The key insight for pushing forward the behavioral sciences is that humans are a new kind of animal. We’re governed not just by millions of years of genetic evolution that apply across the animal kingdom but also by thousands of years of cultural evolution. That is the deep software that plays out differently in different parts of the world.

Knightian Uncertainty

Making decisions in the complex, fast-moving world we live in is imprecise. The future is unknowable and information is rarely complete, so we have to do the best we can.

Knightian Uncertainty, coined by economist Frank Knight in 1921, distinguishes risk from uncertainty in decision-making:

...an ever-changing world brings new opportunities for businesses to make profits, but also means we have imperfect knowledge of future events. Therefore, according to Knight, risk applies to situations where we do not know the outcome of a given situation, but can accurately measure the odds. Uncertainty, on the other hand, applies to situations where we cannot know all the information we need in order to set accurate odds in the first place.

For example, an airline can very accurately quantify the risk of an accident for any individual flight because they have decades of data on plane mechanics, weather dynamics, and the like that influence safety. However, that airline can’t reasonably forecast their business performance 10 years out, because the world and economy is too dynamic to quantify in such a long time frame.

A significant example is the global financial crisis, where banks assumed the risks to their balance sheets to be much more tightly quantified than they actually were, and thus were caught off guard by the scale of the housing bubble.

Check out an overview from MIT for more.

Will behavioral science work for you? Well, it depends...

A challenge in writing and teaching about behavioral science is explaining the nuances of generalizability for the field’s concepts and scientific findings. That is, how to answer the question of “will this work for me?” in response to an interesting cognitive bias or study.

The challenge is that the answer is almost always “it depends,” because human behavior and decision making is too dynamic to apply absolute certainty to predictions. Psychology cannot be as definitive as physics because the inputs and outputs are so variable - the conditions that influence our decision making are too dynamic to accurately predict our actions consistently.

Psychologist Kenneth Gergen actually made this point way back in 1973:

Gergen suggested that the aim of modeling psychological science after the natural sciences was deeply mistaken. It was mistaken because the goal of developing timeless generalizations about your subject was the wrong goal when your subject was human nature. Human beings lived in history and in culture. As history moved and culture changed, human nature changed with it.

This is why it’s best to think of behavioral science as a process versus a collection of answers. I view these fields (and the insights shared in this newsletter) as a toolbox of possible solutions that can be tested to find what works in our own unique situations. From Rory Sutherland:

“…what businesses ask from experimentation is markedly different from what scientists seek. In science, the dream is to uncover a universal, timeless truth or law. In business, we don’t need to be right in general—we just need to make the best decision for the situation at hand.

…

In business, you don’t need to be “right.” You just need to be right enough—or right with sufficient frequency to occupy a lucrative market space. Sometimes all you need to be is less wrong than your competitors.”

We don’t need to know if a nudge or cognitive bias works for everyone, just if it works for us and our goals.

Other stuff

Watching

I haven’t watched many TV shows lately, but was absolutely enthralled by the latest season of HBO’s Industry. I’ve been a fan since the first season, which was a more prestige TV version of bingeable legal/finance dramas, but it’s evolved into something much more interesting.

Listening

I’ve had MJ Lenderman’s new album Manning Fireworks on consistent rotation since its release that month. Here’s a good write up on it from the great music writer Steve Hyden.