3BI: Process vs Outcomes, “Common Sense” Social Signals, and Income Perception

Welcome to my 3BI newsletter, where I share three insights from the world of behavioral science on psychology, decision-making, and behavioral change.

Did someone forward this newsletter to you? Sign up here to have every new edition delivered straight to your inbox.

Process Is as Important as the Outcome

Last week, I wrote about the use cases for current AI tools that I’ve found useful and the overarching theme is that they’re very helpful in accelerating individual knowledge work, not replacing it entirely.

It’s very tempting to use such tools to do most or all of the work for specific tasks or projects, though. We’re wired to get things done as quickly as possible more so than we are to do them in the best possible way. There are certainly some cases where letting AI do all or most of the work may be perfectly reasonable, but, in most scenarios, I think that would be a big mistake.

This is because there’s value in the process of getting things done beyond the resulting outcome that can be hard to quantify. I like how writer and journalist Ezra Klein describes this:

The process of thinking through a problem and engaging deeply with information is important for both our brains and getting better results. There are times when short cuts and automation make a lot of sense, but I think AI tools will make it too easy to do so and hurt knowledge and expertise.

For example, I often sift through a lot of research for my work. When I’m digging into a new problem, I’ll often do a deep dive into the academic literature and industry research to get a sense of how others have tackled it so I can build on that knowledge.

I’ve found AI to be very useful in accelerating this process and making it more efficient. It helps me get started quickly by summarizing what information is out there and how it’s formed into a general consensus. This provides a great starting point to dig into the primary sources and identify additional questions to ask.

This is only useful because I already have a lot of experience doing it myself, though. I’ve learned how to ask the right questions, evaluate the quality of research, and translate information into takeaways and recommendations because I’ve done it so many times. Without that experience, the efficiency gained from the technology would just lead to lower quality output.

I’m worried that this scenario could hurt the ability for new generations to build knowledge and expertise. I mentioned last week that LLM’s are great as a personal analyst for basic functions, which is the type of role young people take in the labor market. There’s already evidence that AI is reducing the amount of hiring for such entry level roles. While it’s feasible for experienced professionals to replace young and inexperienced people with AI for such roles and get similar value, it means that someone is missing out on that valuable experience to learn and build expertise in the first place.

“Common Sense” Can Be a Social Signal

A couple weeks ago, I wrote about how the seemingly “common sense” policy of work requirements for Medicaid wasn’t so straightforward in practice. Despite that evidence, the policy remains relatively popular, though.

Such contradictions have always existed in public policy debates, but have undoubtedly become more common in the last decade as a wave of anti-establishment populism spread over international politics. Old ideas like economic nationalism have returned and previously niche ones like the vaccine opposition have surged as part of a backlash to expertise and institutions.

Why do bad ideas persist despite not standing up to rigorous scrutiny? Why are they becoming more popular at a time when scientific knowledge and information is more robust and accessible than ever?

To understand why, we must first accept that humans don’t make decisions by evaluating evidence and data in an analytical or epistemic way. From Dan Williams at Conspicuous Cognition:

If humans were solitary animals, we would have evolved to approximate the behaviour of Homo economicus, the idealised rational agent imagined in much of twentieth century economics. We would act in ways that are predictable, sensible, and consistent. The characters depicted in Dostoevsky’s novels would be unintelligible to such a creature, except as victims of mental illness.

But we are not. We are social creatures, and almost everything puzzling and paradoxical about our species is downstream of this fact.

As a social species, our survival and thriving has rarely come from individual effort, but reliance on complex networks of cooperation with others. Primitive humans survived in the wild not by the strength and skill of individuals, but the pooling and sharing of skills and resources with tribes. Thus, much of our behavior is driven by the need to gain or maintain access to social networks rather than material self interest.

A focus on social access makes reputational impact the primary motivation of most actions. Making good decisions leads to prestige and status, while poor ones result in shame, humiliation, and ostracization.

When viewing our behavior through that lens, the rise of “common sense” populism and disregard of expertise makes sense as a social movement vs a scientific one:

Experts have produced many theories. Some point to ignorance and stupidity. Some point to disinformation and mass manipulation. Some point to partisan media, echo chambers, and algorithms. And some suggest that the crisis might be related to objective failures by experts themselves.

There is likely some truth in all these explanations. Nevertheless, they share a common assumption: that the “crisis of expertise” is best understood in epistemic terms. They assume that populist hostility to the expert class reflects scepticism that their expertise is genuine—that they really know what they claim to know.

Perhaps this assumption is mistaken. Perhaps at least in some cases, the crisis of expertise is less about doubting expert knowledge than about rejecting the social hierarchy that “trust the experts” implies. Just as Snegiryov would sooner endure hardship than be looked down upon, some populists might sooner accept ignorance than epistemic charity from those they refuse to acknowledge as superior.

Basically, the theory is that “experts” have become viewed as a distinct social class with status and influence that rejects and disrespects the “common man.” Populist leaders both leverage existing sentiment and facilitate it to shift the balance of trust and social status.

This doesn’t mean that the expert class doesn’t have real issues, but implies that the level of backlash and rejection is due to more than just issues with their scientific process. Thus, rebuilding institutional trust isn’t as simple as fixing concrete problems of methods and process, but creating a feeling of acceptance and inclusion for those who reject it.

The good news is that this recognition clarifies the actual problem. The bad news is that the fixes are much less straightforward!

People Think They Are Poorer Than They Really Are

I shared a chart recently on how our perception often misjudges reality. Turns out we don’t just misperceive the prevalence of proportions and occurrences, but also our own position relative to others.

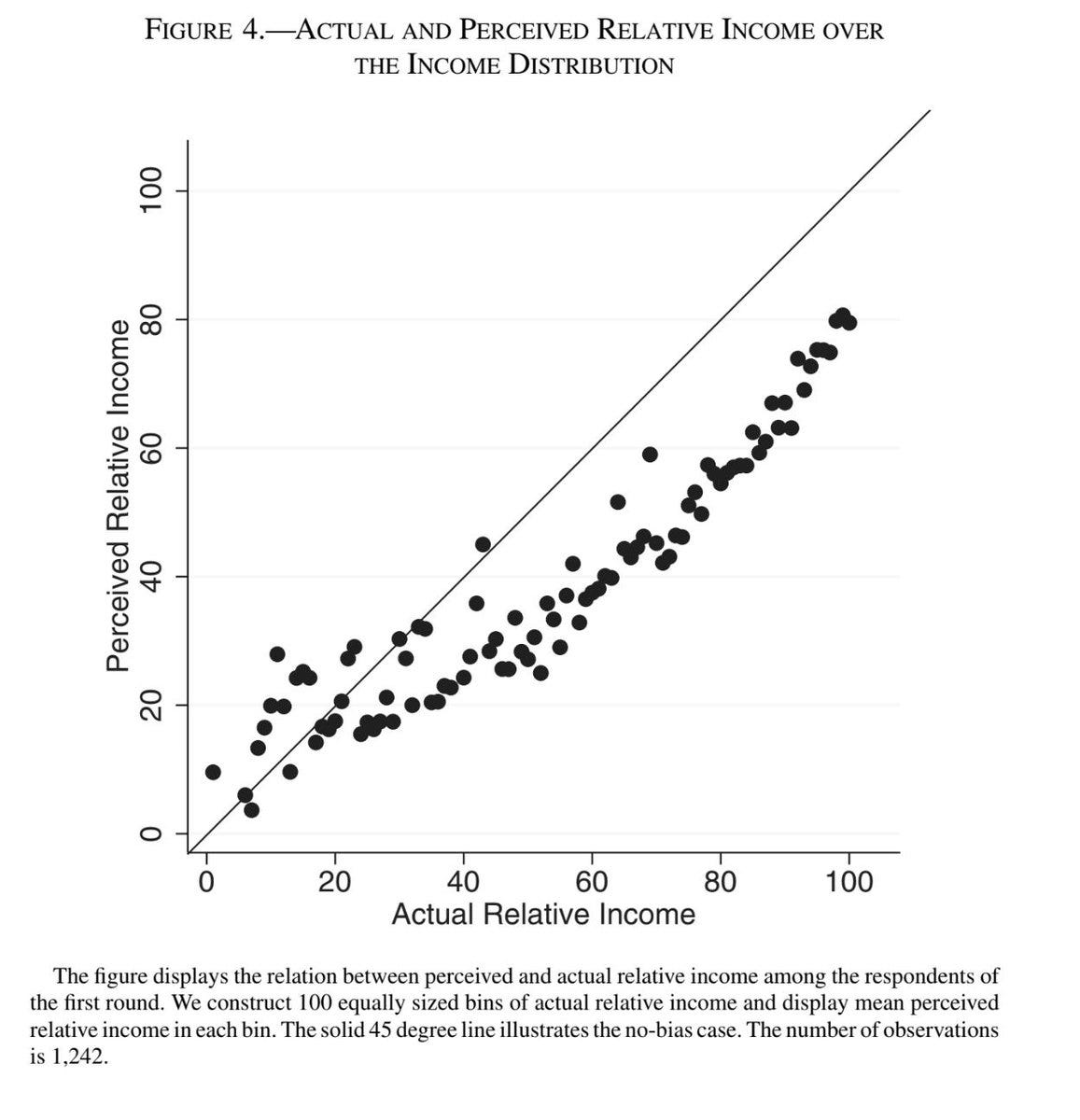

Check out this chart below showing the relationship between perceived and actual place in the income distribution. Dots above the line represent people who think they’re richer than they actually are, while those below see themselves as poorer than reality.

Most people underestimate their income relative to others! Here’s a good graphic demonstrating the same concept:

Perhaps some of this social disconnect is from a limited exposure to people at other levels of the income distribution, as well as a desire to not be a wealthy elite that’s out of touch.

Other Stuff

The world lost two musical legends this week as Sly Stone and Brian Wilson both passed away at the age of 82. RIP to two of the greats. Rolling Stone has good lists of their essential songs:

Sly and the Family Stone at Woodstock:

One of the greatest songs of all time: